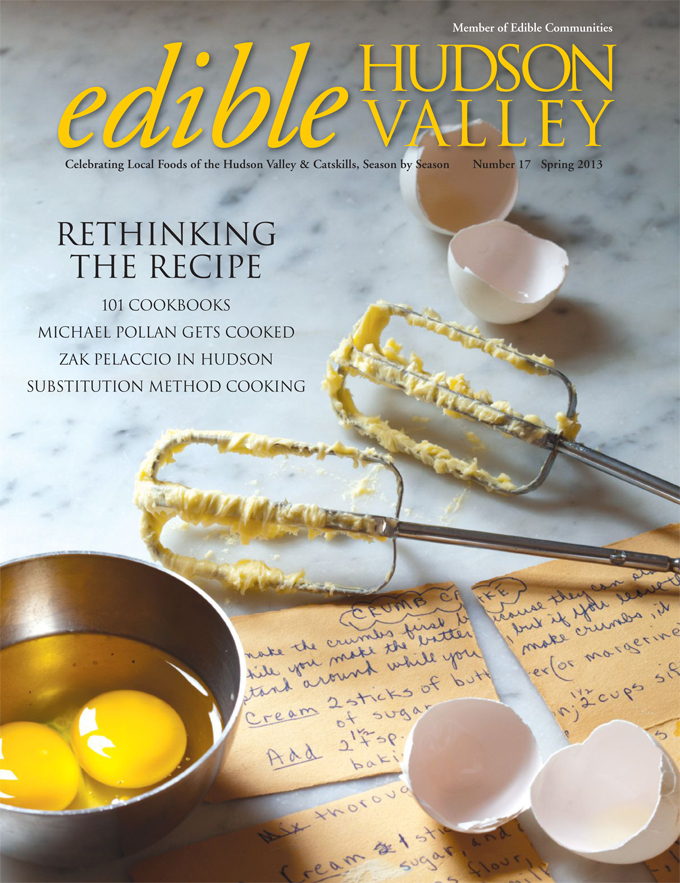

The focus of edible Hudson Valley‘s Spring 2013 issue was “Rethinking the Recipe”. My feature story (“Recipe Liberation Front: To Move Beyond the Written Word”) examines the role of the recipe in pursuit of culinary achievement.

Recipe Liberation Front: To move beyond the written word

By Patrick W. Decker

Text Message (from: Mom) Aug 12, 2012, 9:37 AM

“Good morning my 1st born do you have a good recipe for potatoe soup call you when i get home hope you are having a good week”

Full disclosure: I write and edit recipes for a living. Recipes that find their way into the books and webpages of brands like Rachael Ray, Cooking Channel, Epicurious, Weight Watchers and more. It’s good work if you can get it, as they say.

My mother’s egregious disregard of grammar, punctuation and the proper spelling of “potato” aside, I’ve come to anticipate and cherish her all too frequent flurry of text inquiries to a son whom she views as a recipe database. I’ve gotten queries for all of the hits: 7-layer taco dip, blueberry pie, beef stew, piña coladas and diabetic-friendly cupcakes. The part that continues to perplex me about this correspondence is that these are recipes that I know she has made before. They were all in regular rotation at our table as I was growing up (minus the diabetic cupcakes and piña coladas only on the weekends).

This, I think, begs the bigger question of just how important and indispensible recipes are in cooking and baking. When bounding into intimidating and unchartered culinary territory, then by all means bring a map! But if we’ve made the same thing successfully a hundred times before and could recite the recipe blindfolded in our sleep, or at least feel our way through such familiar terrain, what then compels us to continue to flip open to the same tomato sauce–stained page in the book of your Grandma’s edible heirlooms?

Recipes, in one form or another, have been around since the advent of written communication. Mix item A with item B; give it a little bit of treatment C and (with any luck) you’ll soon be on your way to D-licious. In the modern post-war era of classic “Americana” cooking, moms and housewives from coast to coast shirked off the burden of actually cooking the family dinner from scratch in favor of readymade technological conveniences like TV trays and Salisbury steak.

This generational gap in apprenticeship bred a new wave of homemakers that didn’t learn how to actually cook. You see, up to that point, the “head cook” of the family – who was typically the mother or grandmother – was customarily shadowed by other younger members of the house as culinary wonders were performed and served. Knowledge and skill were endowed by association and hands-on practice. It was only after the apprentices had proven their worth and gotten their hands proverbially dirty that they could then be entrusted with the only other tome holier than the Lord’s: grandma’s recipe book.

The marvels of modern food technology – conveniently portioned and served up in the glossy meat and freezer cases of supermarkets – rendered the Baby Boomers a generation of relatively lazy “dump & stir” cooks. They didn’t break down whole sides of beef or spend hours cleaning vegetables or even baking. They just didn’t have to.

What this created was a vital consumer culture where “recipes” were no longer just cherished gateways to Sunday dinner nostalgia. Instead, recipes oversaturated our magazines and newspaper as commoditized marketing tools to sell more Jell-O and canned green beans and create a semblance of order and control for those lacking basic kitchen confidence. They were built on a foundation of ingredients that were engineered not to fail for an audience of users incapable of creative interpretation or troubleshooting. The notion of cooking according to a recipe became less about understanding how ingredients reacted with one another and more about following the instructions lockstep and exactly as written.

Fast forward a bit and recipes nowadays are as hot a commodity as ever. In our neo-artisanal food bubble, books, blogs, tweets, tastings, shows, showcases, magazines and memes are a hybridized product trying to find a middle ground for seemingly polar opposite audiences with competing desires.

There are people like my mom: the decent cook but diehard recipe acolyte who barely comes up for air while white knuckling verbatim the cooking show offerings. Her go-to resource? My grandma’s worn folio of recipe cards (and also her son’s text inbox, lest ye forget). Her approach? I need a recipe.

Then there’s my hipster neighbors: recreational vegans who shop organic, read magazines printed on 110% recycled matte paper and spend their weekends jarring homemade ketchup painstakingly simmered from local heirloom tomatoes. Their go-to resource? Some Tumblr link they found on their favorite sustainable farming listserv. Their approach? We’ve got a recipe, but we’ll figure it out.

I trust they’ll all figure it out in the end – but to what means?

The Case for Recipe Relevance

As I said before, recipe writing is a big part of how I make my living. It’s my personal belief that recipes are technical documents. Their foundational purpose is to instruct a reader, and prospective cook, how to combine certain ingredients in a given order with a noted amount of manipulation in order to garner a desired outcome. Such recipes are not sexy or overly wordy, they’re practical. They also function as confidence boosters.

“What I really think people hope to achieve from reading a recipe is empowerment.” Those are the sentiments of Tanya Wenman Steel, the editor-in-chief of recipe database megastars Epicurious.com and Gourmet.com. “I always hope they gain greater skills and knowledge, but at the end of the day, I really want them to feel inspired and empowered to just get into the kitchen and make something,” she elaborates. I have to say I agree with her. I know that on the other end of that keypad, every text message from my mom is coming from a place of intent to sit down and create something edible and wonderful. She just needs a bit of a push to get the wheels turning.

Steel’s world revolves around importing new recipes into the system and then exporting them back out to consumers, often in the form of website galleries, e-mail blasts, blog posts, tweets and books. In a world fueled by content, she says that creativity is what makes her industry tick. “Obviously there have been trillions of variations on a chicken recipe, but how you adapt it to your own personal taste and needs is what makes it all so interesting,” she says. It’s the delivery of these bite-size new ideas (or, at the very least, “refreshed” ideas) that keeps food media empires thriving.

Does that then mean that a recipe is immortal, or doomed to planned obsolescence? Steel votes immortal. “That is evident when you find recipes from ancient Greece and Rome. They provide a snapshot of culture at that time and are very much an integral part of social history.” Perhaps much like the intended charting of social trends wrought through the archiving of tweets, the recipe has its own place in the fabric of our identity as a culture. Food trends, after all, are a parallel of a society’s pulse on new cultures, gender roles, environmental issues and more.

Brendan Walsh, dean of culinary education for the Culinary Institute of America, seconds Steel’s notion. Walsh is a key architect in the design of the CIA’s education model, and to him, recipes are crucial tools. “The CIA relates recipes to building blocks. Each can be built onto or off from another to demonstrate how to create complexity and flavor profiles in a completed dish.” They also use them to teach students about the cultures of the world. “Seeing the ingredients and cooking methods that people halfway around the world are using to sustain themselves,” he continues, “gives our students a glimpse into the customs and priorities of cultures that are very different from their own. They’re an invaluable reference tool when teaching.”

Invaluable, huh? I’d agree, but then again I’ve watched my rock star chef of a father-in-law pump out year after year of delicious, multicourse meals without so much as once flipping open a cookbook for reference. And chef and author Michael Ruhlman (also a CIA grad) made a name for himself by publishing his book Ratio: The Simple Codes Behind Everyday Cooking (Scribner, 2009) that eschews the traditional construct of the recipe and instead places its primary importance on a ratio-based equation that purports to answer every and all cooking conundrum. What’s up with that?

The Case for “Just Wingin’ It”

As someone whose job it is to innovate, recipes in my line of work are a constant feed of inspiration whose framework I desperately need to find liberation. In order to create something new from something existing, I need to unlock from my culinary paradigms and read between the lines of what’s not already on the page. I will never forget a lecture I once attended featuring editors from Gourmet magazine – when it was still in print. One of the heads of their test kitchen said, “the way I see it, the food world is finite. There are only so many ingredients we have to work with. It’s simply a matter of juggling all of those balls at once and switching up the order that you catch them in.”

With more people cooking and interested in food as recreation than ever before, the theory that the recipe is simply a guideline, or framework to move beyond, seems to hold some water. It only stands to reason that, the better you get at something, the less you have to refer back to your notes to make sure you’re doing it correctly. Maybe that’s what we find so compelling about watching people cook. Students of a particular trade will dream of aspiring to the level of mastery where a set of instructions is no longer required, where the skill becomes second nature.

Such a philosophy could be said to keep the gears of the professional chef cranking. “Chefs are bad at writing recipes because they work from methods and ratios,” says Walsh. I, of course, prompted him with this question because I see it each and every day – chefs are terrible at writing recipes. “That’s because they’re not writers,” he continues, “the way that many of us [meaning professional chefs] were taught to cook is that your taste buds are your best recipes. Writing something down – locking the process in like that – is kind of a joke because the chef ‘s goal is to achieve balance in flavor. A recipe to him is just a guideline.”

Steel echoes Walsh’s feelings on this. “Chefs cook with inspiration because they already know so much. They don’t need to think of things like how much toasted cumin to add or how many minutes until a tenderloin is medium rare. They just know, and this ‘knowing’ is born from experience. So when you ask them to write it down, they can forget to add simple directions and measurements because they assume so much on the part of the reader.” “Plus,” argues Walsh, “who’s to say what ‘correct’ is? Head on over to the Italian Heritage Center and ask the room for a tomato sauce recipe. You’ll have a hoard of grandmothers rush you with 55 different versions of a ‘perfect’ tomato sauce.”

Taking a Place at the Table

All right, heady philosophical stuff aside, there’s still “real life” at work in all this. From the cursory need for Tuesday night dinner to the mapping of cultural trends, the intent of a recipe fills many a void for many different people. What the culinary elite in pursuit of mastery may call a crutch, and the beleaguered home chef in search of help may call a lifesaver, I call empowering.

Like anything in life, we all have different skill sets and abilities. Those well seasoned in the culinary arena may turn up their nose at people who need a recipe to make such rudimentary things as roast chicken and potatoes. Personally, I’m a culinary school graduate who looks up recipes constantly for inspiration, variation and affirmation. My mom, at the other end of the spectrum, just wants to make something nice for the girls at work and is looking for a new idea that she could follow to the letter.

Whether perceived as confining or inspiring, perhaps opening up Grandma’s sauce-stained recipe book isn’t about creating perfection or admitting defeat. It’s about just doing it in the first place.

This piece originally ran in edible Hudson Valley Number 17 (Spring 2013).